In the Yoruba pantheon of elemental deities called orisa, there is one who remains a mystery to most people in spite of mans’ inquisitiveness and desire to understand him. Reviled, respected, misunderstood, revered, maligned, praised, trusted, feared, railed against by Christian preachers, supplicated on bended knee by Yoruba Babalawo priests of Ifa and traditional believers seeking his aid, Esu has the last laugh as all humans and creation dance to his beat of life.

In the Yoruba pantheon of elemental deities called orisa, there is one who remains a mystery to most people in spite of mans’ inquisitiveness and desire to understand him. Reviled, respected, misunderstood, revered, maligned, praised, trusted, feared, railed against by Christian preachers, supplicated on bended knee by Yoruba Babalawo priests of Ifa and traditional believers seeking his aid, Esu has the last laugh as all humans and creation dance to his beat of life.

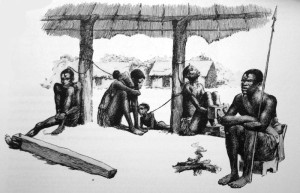

The worship of Esu originated with the Yoruba people in the region now called Nigeria. Taking center stage in the Yoruba creation stories, Esu is also referred to as Elegbara by the Yoruba who populate the coastal region. Translated to English, Elegbara, one of Esu’s many praise names, means “the mighty and powerful one”, or, “the mighty one of wonders”. These praise names, called oriki by the Yoruba, are used to describe the qualities and powers of Elegbara. They can also be found in the lyrics of his songs and in the sacred verses called ese, recited much like poetry, which are gathered under odus. These odus are arranged as chapters, as divination signatures which comprise the 256 marks of the Ifa corpus, the oral bible of the Yoruba.There are dozens of names, as there are dozens of manifestations of Elegbara. He is also known as Dagunro, Goroso, Lukuluku and Apagbe. Elegbara can be difficult to describe. As Papawara, “the quickest and fastest one”, he slips in and out of definitions with alarming speed, quickly concealing what was thought to be concrete, open and fixed, then, with absolute glee, reveals himself in a completely new and baffling transformation.

The adjectives and phrases that can be used to describe Elegbara are varied but are used consistently among West African traditional cultures that have an Elegbara figure among their gods. He can be described as a disruptor of order, ironic, a master linguist, ambiguous, a conciliatory peacemaker, the possessor of a huge phallus with a ferocious appetite, a satirical mimicker who finds our “hot buttons” and pushes them with childlike insistence, and as one who both hides and reveals secrets. Elegbara is a master of change, of chance, a divine alchemist who only needs to blink his eyes or speak and it will be so. His name of Esu Odara translates as “Esu the magician”, or, “One who can do and undo”, and adds weight to his reputation as a performer of magical feats.

In the odu of Osetura we are shown how slippery and difficult Elegbara is to pin down:

Peri-pokun,

Pokun-peri

Esu bambi

A dia f’Akon omo oluwara oje….

Pursue him here

He is over there

Follow him there

He is back here

So revels Esu the Trickster

In confusing detour

Thus declared the Ifa oracle to Crab

Who hides from hole to hole in marshes.

It is not just in West Africa but in every culture of the world that one finds a similar deity or god like Elegbara, many times referred to as a “trickster” due to his sense of humor, command of all languages, love of mischief, ability to shape-shift and his tendency to play tricks on unsuspecting humans.

In West Africa, the worship of Elegbara spread from the Yoruba to the Fon who populate parts of Benin, Togo, Cameroon, and southwestern Nigeria. He is known as Legba to the Fon, as Ananse to the Ashanti people in Ghana and as Ogo-Yurugu to the Dogon living in the central plateau of Mali. In Brazil, Exu, as his name is spelled there, goes by many names that describe his qualities and the manner in which he works. Some of these are Exu Tranca-ruas ( Esu close/lock-the-roads), Exu da Meia-noite (Esu of Midnight) and Exu Caveira (Esu Skull i.e. of the Tombs). Brazilian devotees of Exu also work with his female counterpart (since every orisa has male and female qualities), known as Pomba-Gira, which is a complex mix of a female egun linked with Exu, popular in the Xango (Sango) cult of northeastern Brazil. These female Exus, predominantly manifested by women, are known for their powerful expertise in the love affairs of men and women and are unparalleled seductresses who offer their help, advice and recipes to the faithful. Santeria and Lucumi devotees in Cuba use the name Elegua for Elegbara, while New World Voudun practitioners call him Papa Legba or Legba Atibon and another manifestation of Elegbara, Kalfou, in Haiti, and Papa La Bas in North American Hoodoo. Europeans were no strangers to “trickster” gods and the Greeks had the god Hermes, while the Romans had Mercury, a messenger of the gods with winged sandals on his feet. A great number of Native Americans in the United States worshiped or still do worship the coyote, a type of jackal, as their trickster deity. Other tribes worshiped the wily rabbit, crow or raven.

Professor Byrd Gibbens, University of Arkansas, U.S., states that, “Many native traditions held clowns and tricksters as essential to any contact with the sacred. People could not pray until they had laughed, because laughter opens and frees from rigid preconception. Humans had to have tricksters within the most sacred ceremonies for fear that they forget the sacred comes through upset, reversal, surprise. The trickster in most native traditions is essential to creation, to birth.”

Indeed, Elegbara is the life force pumping in our veins, he is the electrical spark in our hearts which gives us life, he is the stream of semen which impregnates, he is impetus, he is forward movement, and all along that forward movement of life he dances circles around us, laughing when we take things too seriously, warning us of our weaknesses and infractions, poking fun at us, but always looking to combat darkness and bring about balance and harmony after we have stumbled, fallen, scraped our knees and risen again to face another day. Elegbara has existed since the beginning of time. Bearing the name Lagemo Orun, meaning “sacred child of heaven”, he was created by Olodumare, the Supreme Creator, and holds a position of unchallenged importance and authority. Though having divine origins, many of the ese of Ifa divination speak of Elegbara as having lived on earth.

There are many localities where Elegbara supposedly walked the sacred land of the Yoruba. The first of these is the spiritual cradle of the Yoruba race called Ile-Ife in current southwestern Nigeria. This is the area where Orunmila and the orisas first descended to earth to take up residence and populate the world which had been created by Olodumare and Orunmila. Ese of Ifa also place him on a mountaintop near Igbeti, close to the Niger River. Other ese take him to Ketu of the Dahomey kingdom, now the present day Republic of Benin. There are also reports that he was worshiped or lived in a village called Iworo near Badagry on the coast of what is now Lagos State, Nigeria. Researcher Peter McKenzie identifies a sacred grove in Iworo as the most famous site of Elegbara worship, but claims that this shrine was destroyed in 1863 by Governor Glover of Lagos. Present day worship of Elegbara in Nigeria is strong in Osun and Ondo State but he is worshiped throughout Yoruba land.

As Olodumare’s loyal and faithful servant, Elegbara works under him and alongside Orunmila, punishing anyone who does not carry out the wishes of Olodumare, who does not make the prescribed sacrifices, or who does not live within the godly principles laid out by Olodumare. He is the most powerful and important deity amongst the orisa as he must be acknowledged first in all rituals by humans and all orisa alike. His praise name Alajiki tells us that he is “the one to be addressed first” and his name Akeregbaye tells us that he is “small but in control of the whole world”. He is a force to be respected and no one should ever think they are clever enough to get the upper hand with Elegbara.

Elegbara and Orunmila are inseparable friends, and of all the orisas, Orunmila is the one who knows how to handle the dynamic power, energy and uncertain temperament of Elegbara. Orunmila is the embodiment of the wisdom of Ifa and head of the Ifa priesthood. It was Orunmila who was sent to earth by Olodumare to aid in the creation and development of earth and foster the human beings living there. Olodumare gave to Orunmila the ability to divine his will by using the sixteen sacred palm nuts, so that man would not suffer anymore.

Ese of the odus speak of Elegbara tagging alongside Orunmila as a kind of learner priest as he walked the land divining, but it is safe to say that Elegbara was created out of necessity by Olodumare. He arrived already possessing his great destiny to fight for anyone who has offered the appropriate sacrifice against the powerful Ajogun Orun. These negative forces are Death, Disease, Loss, Destruction and Lawsuit, who wreak havoc in humans’ lives. The praise names of Alaakalu, “one whose greatness is manifested everywhere”, and Amonisegun Mapo, “he who is all-knowing and has powerful medicine”, attest to his capabilities and superiority over the Ajogun. It is this incomprehensible ability to be both big and small at the same time that confounds normal human sensibilities. Elegbara thumbs his nose at physics and makes us rub our eyes more than once as we try to accurately perceive him. The following praise chant attempts to explain his size:

Esu sleeps in the house

But the house is too small for him

Esu sleeps on the front yard

But the yard is too constricting for him

Esu sleeps in the palm nut shell

Now he has enough room to stretch at large….

Carved statues and ese describe Elegbara as a short man with a beard, pointed teeth, polished skin black as night, and with the curious habit of walking with a limp, due to his having one foot in the world of the humans and one foot in the spiritual realm. His statues sometimes portray him as holding a calabash in his left hand in which the divine ase of Olodumare rests. This ase, pronounced ah-shay, is the power of divine command and he has the discretion to use it as he sees fit. At other times he is seen with a magic bag or gourd, or a type of wand in hand. This takes the name of Ado Asure which contains fortunes or magic inside. In some verses it is said that he points his wand and whatever he wishes comes to pass. Elegbara is said to have eyes in the front and back of his head as shown in his carved statues, by the hook-like outgrowth attached at the back of his head. It is here where his other eyes are said to be. This can be thought of as having the ability to see into the future or the past, and also as having foresight and hindsight, something we need in our daily lives as we make split-second decisions which can have far reaching consequences. Clearly, this is Elegbara’s territory.

Carved statues and ese describe Elegbara as a short man with a beard, pointed teeth, polished skin black as night, and with the curious habit of walking with a limp, due to his having one foot in the world of the humans and one foot in the spiritual realm. His statues sometimes portray him as holding a calabash in his left hand in which the divine ase of Olodumare rests. This ase, pronounced ah-shay, is the power of divine command and he has the discretion to use it as he sees fit. At other times he is seen with a magic bag or gourd, or a type of wand in hand. This takes the name of Ado Asure which contains fortunes or magic inside. In some verses it is said that he points his wand and whatever he wishes comes to pass. Elegbara is said to have eyes in the front and back of his head as shown in his carved statues, by the hook-like outgrowth attached at the back of his head. It is here where his other eyes are said to be. This can be thought of as having the ability to see into the future or the past, and also as having foresight and hindsight, something we need in our daily lives as we make split-second decisions which can have far reaching consequences. Clearly, this is Elegbara’s territory.

He is sometimes depicted in statues as having a huge, over-sized, erect phallus, linking him with fertility and also the potentially dangerous relations between men and women. In Brazil, one of the many names for the African-based religions is Candomble and there is a terreiro (sacred house where the orisas are called down), of Candomble in Itapoa, Bahia State, Brazil, that has a wooden phallus carved from a fairly large tree trunk. Those possessed by Exu can be seen sitting with it between their legs, smoking, drinking and giving advice to the people seated around him and seeking his favor. There are risqué comments, laughter and clever joking in between the serious words.

There is a common saying amongst the Fon of West Africa, who imported Elegbara from the Yoruba: “Legba everywhere dances in the manner of a man copulating.” Anthropologist Melville J. Herskovits (1895-1963) was a pioneer in research on African cultures and saw Legba dance in the flesh. American born, he traveled to most of the countries with an African presence in the New World and produced ground breaking ethnographic research while in Africa. He was an advocate of African self-determination and he devoted his life trying to destroy the myths that the beliefs and cultures of Africans were primitive and that Africans had not made a contribution to world history.

His research on the Fons’ Legba and his peculiar dance was documented by later researcher Robert Pelton, whose quoted work follows: “On the next day “Legba” makes his first appearance. He is represented by a young girl dressed in a purple raffia skirt and a purple straw hat, and on the final days of the emergence ritual this “Legba” leads the dancing of the novices.” Herskovitz wrote about Legba in the body of the young girl: “dancing toward the drums. When she reached the drummer, she put her hand under the fringe of raffia about her waist… and brought out a wooden phallus…This was apparently attached in such a way that it would remain in the horizontal position of the erect male organ, and as she danced…toward a large tree where many women were sitting watching the ceremony, … they ran from her, shrieking with laughter, and they were made the butt of many jokes by the spectators.”

It is certain that these kinds of antics were looked upon with horror by the first European missionaries who arrived in West Africa and who dared witness such “primitive” and “heathen” gatherings. In his book, A History of the Yorubas from the Earliest Times to the Beginning of the British Protectorate, Samuel Johnson, an Anglican priest and missionary who claimed descent from the Alaafin Abiodun of Oyo, depicted the worship of Elegbara in the early to mid 1800’s as thus: “… Esu or Eleghara. — Satan, the Evil One, the author of all evil is often and specially propitiated. Offerings are made to it. The representing image is a rough lateritic stone upon which libations of palm oil are poured. It is superstitiously believed that the vengeance of this god could be successfully invoked upon an offender by the name of the person being called before the image while nut oil is being poured on it. The image of a man, with a horn on its head curving backwards, carved in wood and ornamented with cowries, is often carried by its devotees to beg with on public highways. Passers-by who are so disposed may give each a cowry or two, or handfuls of corn, beans, or any product of the field at hand, as he or she may choose. This curved headed figure is called ” Ogo Eliggbara “—the devil’s club.”

Contrary to the Euro-Christian view defaming him as the ruler of hell and bearing the name of Satan, or, Devil, the translation of Esu means “the divine messenger” while his name Elegba translates to “spirit of good character”. Both names are hardly reminiscent of the evil deeds and qualities attributed to Satan throughout the ages. Christian missionaries have loudly denounced Elegbara and all who worship or profess belief in his kind as pagan or “fetish” for almost 200 years. Missionaries already had a foot in the country in the early 1800’s and the Christian Missionary Society pushed further in to the hinterlands in 1841 when Sir Thomas Fowell, accompanied by Yoruba born preacher and linguist Samuel Ajayi Crowther, made an investigative trip called the Niger Expedition that was to prepare a “…religious, economic, and civilizing mission…” along the Niger.

The pendulum has now started to swing back in the other direction with noted scholars and important public figures defending traditional Yoruba culture, and more importantly, the peoples’ right to worship the gods of their ancestors in peace, asking for a more enlightened and civil attitude from modern-day “preachers of the cloth”.

Funso Aiyejina, Professor of Literature at the University of the West Indies, St. Augustine, Trinidad and Tobago, gave an interesting lecture at the National Theatre in Lagos in 2009, organized by the Centre for Black and African Arts and Civilization (CBAAC). The title of his lecture was ‘Esu Elegbara: A Source of an Alter/Native Theory of African Literature’ and in it he blamed the late Bishop Ajayi Crowther for having chosen to translate the word Satan as the Christian meaning for Esu when he translated the Bible into Yoruba. A more appropriate use of words would have been to use Awon Aye, evil powers, to describe Satan. Aiyejina also pointed fingers at Africans for allowing him to translate the word erroneously. He said, “If Africans had been less trusting and more cynical and suspicious, they would have wondered why the same translators of the Bible who saw nothing wrong with equating Satan with Esu, did not find a near-equivalent Yoruba deity for Jesus Christ, instead of Yorubanizing his name into Jesu Kristi…If Satan translates into Esu because of some perceived incidental similarities between the two, how come Jesus does not translate into Orunmila, given the fact that Orunmila is as proverbial, wise, calm, peaceful and forbearing as Jesus?” he asked. He raises an important question, central to all people who call themselves Yoruba and who now in modern times find themselves at odds with their family ancestors’ past and with the imported Western cultures and values which have been steadily eroding the traditions of this land since the first Europeans set foot on the African continent.

It has reached such proportions that UNESCO (United Nations Educational Scientific and Cultural Organization), has had to step in and offer protection to the Ifa divination oral tradition under the umbrella of the 2003 Convention for the Safeguarding of the Intangible Cultural Heritage. In Convention 2005, the Ifa Divination System entered the protected list as a Masterpiece of the Oral and Intangible Heritage of Humanity. Measures are being taken to ensure that the tradition is kept alive along with the Yoruba language.

The heart of the Yoruba Ifa tradition and theology is the act of divination with the sixteen sacred  palm nuts of Ifa, the casting of the opele and of the sixteen cowrie shells. Olodunmare and Elegbara are called upon to open every divination session, before the other orisa are named. Elegbara’s face is depicted on almost every wooden opon used for Ifa divination, with his eyes and mouth being the central focus carved into the wood. He takes the central position at the top of the board which lies opposite the seated Babalawo, the Ifa priest, reminding us that it is he that travels between orun and aiye, heaven and earth, possessing the divine ase that will allow any sacrifice or work carried out to come to fruition. Elegbara is the eyes and mouthpiece which carries to Orunmila the vision of the past, present and future and Orunmila in turn makes sure that Elegbara is always given his share of every sacrifice offered, no matter how big or small, and he is served first of any food or drink being offered. Failure to comply and make sacrifice after divination ensures that Elegbara will simply stand by and watch impassively as a perhaps negative fate, of which the Ifa oracle warned, comes to pass. Conversely, we will also not attract the positive blessings which Ifa predicts for us due to non-compliance. Elegbara both sympathizes and at the same time disregards the human condition of man.

palm nuts of Ifa, the casting of the opele and of the sixteen cowrie shells. Olodunmare and Elegbara are called upon to open every divination session, before the other orisa are named. Elegbara’s face is depicted on almost every wooden opon used for Ifa divination, with his eyes and mouth being the central focus carved into the wood. He takes the central position at the top of the board which lies opposite the seated Babalawo, the Ifa priest, reminding us that it is he that travels between orun and aiye, heaven and earth, possessing the divine ase that will allow any sacrifice or work carried out to come to fruition. Elegbara is the eyes and mouthpiece which carries to Orunmila the vision of the past, present and future and Orunmila in turn makes sure that Elegbara is always given his share of every sacrifice offered, no matter how big or small, and he is served first of any food or drink being offered. Failure to comply and make sacrifice after divination ensures that Elegbara will simply stand by and watch impassively as a perhaps negative fate, of which the Ifa oracle warned, comes to pass. Conversely, we will also not attract the positive blessings which Ifa predicts for us due to non-compliance. Elegbara both sympathizes and at the same time disregards the human condition of man.

Without Elegbara, Orunmila would not be able to carry out the will of Olodumare through Ifa divination and ensure properly delivered sacrifices. The results would be disastrous for humans on earth. As the ultimate controller of our fate, Elegbara has a hand in our destiny, working in a type of mutually beneficial partnership. We can either use Elegbara to our advantage to clear all evil and misfortune from our road of life, or ignore him and suddenly find we are stepping off into a bottomless abyss.

Praised as Osetura, the gatekeeper, we pray that he takes our wishes, requests and sacrifices to the invisible realm of heaven where they can be fulfilled, restoring harmony in our lives. One of his praise songs is Alare na ode orun, meaning “the middleman between heaven and earth“, which shows us that the intersecting lines of the material and spiritual planes are his natural home. Elegbara owns the crossroads, materially, spiritually and metaphorically. Each road leads to an exact center, a ground zero where our cosmic karma either comes in the form of Elegbara to club us on the head, or a new road appears to lead us to spiritual and material well-being and insight.

Esu Laalu Omokunrin Ode is “the noble man who dwells at the cross-roads” and a verse from the Odu Ika Meji states:

Esu Laalu Omokunrin Ode is “the noble man who dwells at the cross-roads” and a verse from the Odu Ika Meji states:

Igbori nile Eegun,

Iranje nile Oosa,

Ita gbangba Elegbara.

The departed ancestors were first revered in the city of Igbori,

Orisanla was first venerated in the city of Iranje;

The mighty one of wonders has his shrine

In any public place where three or more roads cross.

ESU ELEGBARA-SACRED CHILD OF HEAVEN

Historically, Elegbara is the protector of earthly crossroads, towns and homes. His various shrines of chunks of laterite or simple mounds of earth with scattered offerings can be found at city gates, outside domestic doorways and shrines and in public markets where the faithful offer palm oil, bits of bitter kola, kola nut or other pleasing offerings for Elegbara. He has an insatiable love of palm oil and if nothing else is available, this is the offering which pleases him most. He also accepts he-goat, cock, fried bean fritters, mashed yam, clean water, and catfish amongst others.

It is interesting to note that even in the New World, the foods and sacrificial preferences and names of the Old World orisas have remained overwhelmingly intact. This is not surprising as the transatlantic slave trade carried away millions of West Africans who took their belief systems, deities and their food preferences with them to the New World. Central to food offerings is the ever-flowing red palm oil, epo pupa, or azeite de dende, as it‘s known in Brazil. Brazil has an abundance of foods typical to Nigerian soil counting yam, cassava, the okro of Sango, various beans delectable to Oya and hot peppers amongst the orisas’ menu. The akara of Nigeria is spelled acaraje in Brazil and it has remained one of the preferred foods of Oya. Strong alcohol, bitter kola, kola nut, hen, cock, he-goat, she-goat, sheep, ram, and bull; all of these things are offered in the New World.

The sometimes lusty and abandoned manner in which Elegbara dances and the colors in which he is clothed are also intact when compared with West Africa, with the colors red and black or black and white making up his sacred wardrobe in the New World. In Brazil, Exu delights in being set free to roam the streets to dance in the crossroads, be it a road made of asphalt or of earth-under the full moon or the hot midday sun. Lucky is the person who witnesses Exu set loose to dance on the pounded red earth with rattles made of gourds clacking about the ankles, a leather cap affixed to his head. Some terreiros clothe Exu in a handsome satin cape covered in sacred symbols and slung about the shoulders, which adds to Exu’s striking presence on feast days. These feast parties, or giras (making reference to the circle of devotees dancing to the drums and awaiting possession), usually take place once a month honoring one or more orisa and they are no more remarkable in the eyes of society than a child’s birthday party. It is not uncommon to see young mothers breastfeeding babies, young men and people of all ages up to octogenarians enjoying the drumming and the spirited dancing of the orisa. There are also large communities of orisa worshipers in the United States with a huge presence in the states of Florida, New York, California, and Louisiana. The coastal islands off Georgia and South Carolina have sheltered the descendants of slaves for centuries with strong African traditions surviving there.

Though there are many regional differences in how Elegbara is worshiped in ritual form, there is a common thread that runs through all sacred houses of worship, no matter their location on the planet. This tells us that belief in the orisa is very much alive and well in spite of the faithful sons and daughters having been forcefully carried away across the waters from the birthplace of the orisas.

From the years 1650 to 1900, almost nine million slaves were taken from the Gold Coast, the Bight of Benin, the Bight of Biafra, and West Central Africa. The great majority landed in Brazil, with the rest going to the United States and the islands of the West Indies in the Caribbean such as Cuba, Jamaica, present day Haiti and Puerto Rico, Trinidad-Tobago, Curacao and Antigua. A  small number of captives were taken to Mexico and to Columbia in South America. Later migrations led to orisa worship and syncretism with the Catholic church in various countries such as Honduras, Venezuela, and French Guinea amongst others. During the twentieth century, orisa, and principally Ifa worship, spread to Argentina, Canada, the United States, Mexico, Russia, Japan, Denmark, Finland and many other countries, showing that so-called advanced and literate societies have found spiritual value and meaning in African-based religious traditions, specifically the Yoruba traditions, while so many Africans have tried to purge these from their family lineages and their own modern day lives.

small number of captives were taken to Mexico and to Columbia in South America. Later migrations led to orisa worship and syncretism with the Catholic church in various countries such as Honduras, Venezuela, and French Guinea amongst others. During the twentieth century, orisa, and principally Ifa worship, spread to Argentina, Canada, the United States, Mexico, Russia, Japan, Denmark, Finland and many other countries, showing that so-called advanced and literate societies have found spiritual value and meaning in African-based religious traditions, specifically the Yoruba traditions, while so many Africans have tried to purge these from their family lineages and their own modern day lives.

For lack of a better or more creative phrase, a global village best describes the world we are living in today, with religious adherents of many skin colors, languages and nationalities praising the names of Olodumare, Elegbara and the orisa. In just a few hundred years humanity witnessed a huge migration, with a resultant subtle shifting of thought, as the slaves of the Middle Passage disseminated what can only be called a non-rational and “electro-dynamic” approach to spirituality and of place in the order of the universe. That universe is a flexible, gossamer web which shimmers like the night sky. Within the streams of living energy that make up the web are all the elements, the planets, stars, galaxies, orisa, humans, plants, animals, minerals and vegetative life. We are all inter-connected and the Ifa divination system accesses the plant, animal and mineral wisdom that Olodumare, all the orisa and the elders handed down orally to relieve our suffering. For every problem known to man, there is a solution within the chanted ese of Ifa. By manipulating the cosmic strings of the web through the power of Elegbara, the Ifa priests, who embody Orunmila, align us with the universe, bringing about order, harmony and victory for us on earth. Happiness and peace enter our hearts and it is there in the human heart where Elegbara resides.

He teaches us how to behave, how to make proper choices with our heart that knows, or should know, the difference between right and wrong, good and evil. He reflects the positive and negative forces which exist in the world and within all humankind. He is the ultimate tempter, offering us everything we selfishly desire with one hand, and with the other he makes ready to club us on the head. He will give us just enough rope so that we can either tie a noose and hang ourselves, or we can use the rope to help lift ourselves up out of our troubles. These are the lessons Elegbara gives us as we live out our days on earth.

Our blue planet is spinning at 1,000 miles an hour, rotating around the sun in a dance of 67,000 miles an hour, nestled in a twinkling galaxy called the Milky Way that contains about 100 billion stars. As we move within the solar system, our galaxy is also drifting through the darkness of intergalactic space where an estimated 100 billion galaxies are scattered throughout the visible universe. In the face of this incomprehensible and limitless enormity, man must find a way to rectify himself, to justify his presence in the order of the universe and as he stands staring up at the night sky, somewhere on the planet Elegbara is dancing barefoot on red earth, laughing.

©2009 – 2016 by Farin da Silva, All Rights Reserved. Pursuant to the Copyright Act of 1976 and subsequent amendments, codified as 17 U.S.C. §§ 101-810, the works contained within are protected by United States laws and by international treaties. This includes the literary and pictorial works created by Farin da Silva contained herein, as well as any other original works of authorship fixed in any tangible medium of expression. The unauthorized copying, distributing, displaying, or production of derivative works is strictly prohibited by Farin da Silva. Copyright infringement may subject you to civil liability of a minimum of $750 per infringement for statutory damages, as well as the costs incurred to enforce these rights. 17 U.S.C. § 504. A court may award up to $150,000 per infringement. This copyright holder takes copyright infringement seriously and does enforce their rights.

PHOTO CREDITS: Left-‘Esu-Elegbara Staff’, image reproduced with permission from thebrooklynartmuseum.org

Center-‘Two Esu Figures’, Image reproduced with permission of the Aspen Art Museum. From the AAM catalogue The Shaman as Artist/The Artist as Shaman (1994), published in conjunction with the exhibition of the same title (February 10 – April 10, 1994).

Right-‘Esu Figure’, image reproduced with permission from the brooklynartmuseum.org

Copyright protected by Digiprove © 2016 Farinade Olokun

Copyright protected by Digiprove © 2016 Farinade Olokun